I can’t take the credit for this one and I’m not even sure who can. I found it recently on an untitled word document, among a pile of papers that I had obviously put to one side to read later. Well I’m glad I finally did read it and I commend it to you, and if anyone can identify the author please let me know.

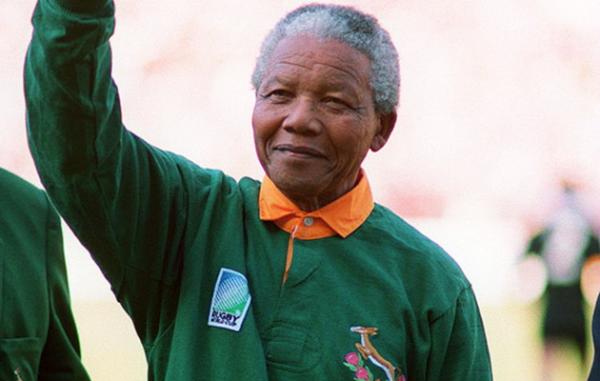

It begins with a reflection on that iconic moment when Nelson Mandela, as the new President of South Africa, put on the green jersey of the nation’s Rugby team during the Rugby World Cup that took place in South Africa in 1995. As the author notes, it was a hugely symbolic gesture, in effect saying “we are all South Africans now”, which demonstrated both Mandela’s power as president, but also his love for all the people of the new South Africa. It meant getting the balance right between authority and inclusivity, between power and love. So here it is.

‘As leaders we face similar challenges. Our context is changing and those who we lead are watching us. As more is expected of us, what kind of leadership is needed from us in these times of change? Using the analogy of ‘power’ (the drive to get the job done, to push things to a conclusion) and ‘love’ (the drive to connect things, to bring people together, to unify), as leaders we cannot choose one or the other, we must choose both.

There are four tensions we need to navigate when balancing these elements in our leadership.

1. ‘Being a pacesetter’ versus ‘Being a coach’

Daniel Goleman argues that although pacesetting is an important leadership style and is sometimes just what is needed, it won’t provide lasting improvements unless you adopt other leadership styles. Drawing on the work of Goleman, as leaders, if our only style is pacesetting we may find that we have stepped out on our own but that nobody is following, instead they are criticising us from the side-lines. But the answer is not necessarily to reduce the pace, it is to also have strategies to support those we lead in coping with the pace, to be a coach as well as a pacesetter.

2. ‘Challenging’ versus ‘Openness to being challenged’

Great strategists don’t always take people with them. The best leaders must be extremely challenging, but alongside this, we need to show that we welcome challenge ourselves and can model a more open and engaging style of leadership. The best leaders are very challenging but they also don’t take themselves too seriously. They encourage their teams to question their thinking and they go out of their way to make it okay for their teams to challenge them. They ask questions, they are curious. They don’t believe they have all the answers. They involve their staff in crucial decisions and encourage them to test new ideas.

3. ‘Being competitive’ versus ‘Being collaborative’

Our role is to do the best we can to improve our service areas and organisations and this, of course, means that there is competition within and between organisations. Although sometimes it’s not fashionable to admit it, competition stops us from being complacent and keeps us on our toes. Accountability and competition are good things and should be welcomed by all those who want to raise aspirations and help communities to achieve their potential.

However, collaboration is just as important and in fact, without it, all we will get is greater variation in quality. Some will get better and do really well, but overall the system will not improve. The right kind of collaboration is key though, it’s not about huddling together and endorsing each other’s views and practices, it needs to be inclusive but also focused on outcomes, on raising the bar and achieving real solutions for improvement.

4. ‘Being consistent’ versus ‘Being adaptive to context’

To what extent can solutions and good practice be applied across the board or are they context related? If you have a tried and tested system that has clearly worked well and delivered results why should others not use that system rather than try to invent their own, especially if this is based on sound evidence? But there is another side to this, especially when it comes to leadership: context does matter.

We need to have leaders who can adapt their leadership to different circumstances. We have to ask ourselves whether the leadership approaches that have worked for us in the past are still going to work for us in the future, in a world that is very different from the one we have now (whether we like it or not). And, if we do decide that we do need to adapt our leadership approaches, how do we make that happen? It certainly isn’t easy. We need to adapt to support the new leadership behaviours rather than the old ones.

In order to navigate these four tensions, it’s time for us to step up and build a new spirit of professionalism. As the whole system shifts and turns, more than ever before we need leaders who are demonstrating authority, pace and a commitment to systems that work, and are combining it with inclusivity, collaboration, and contextualisation: leaders who are stepping up to lead a self-improving system.

The real watershed moment we are living through is because this is an era that won’t be defined so much by the financial and policy changes taking place, unprecedented though many of them are, but by what we, as leaders, make of those changes, how we seize the opportunity to redefine our approach and to ensure outcomes improve.’